Olympic gold for barefoot runners Bikila

60 years ago, Abebe Bikila was the first Ethiopian to run to marathon gold – without shoes. His Olympic victory in Rome, full of political symbolism, was the start of a new era. And saved his own life.

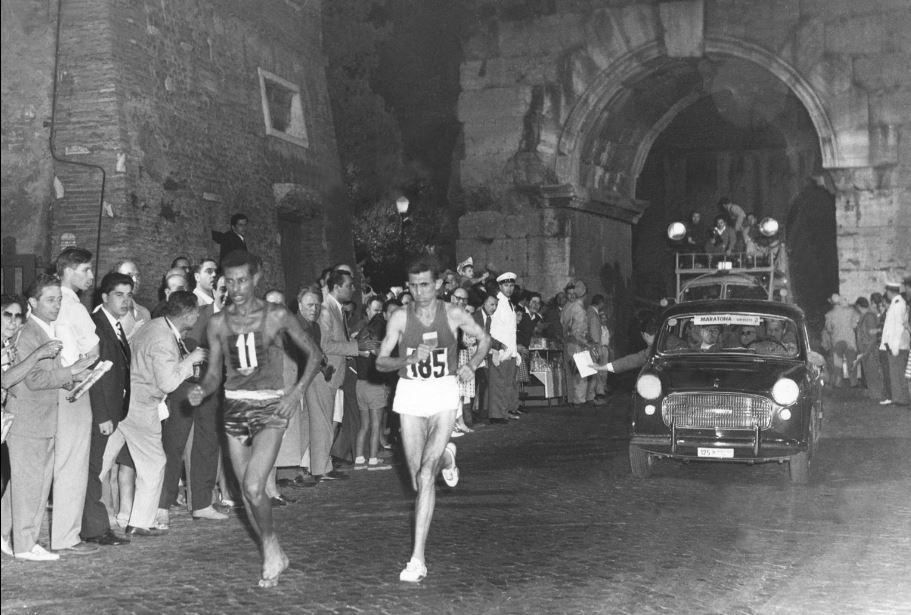

The athletes crowd close together in the afternoon heat. Some are joking with each other, others are staring straight ahead. The skinny man in the green jersey with the number 11. He can hardly be a competitor – he doesn’t even wear shoes.

Abebe Bikila took only one tattered couple from Ethiopia to the Summer Olympics in Rome in 1960. Since he couldn’t find a new pair there either, he decided to run barefoot, as he has been used to from childhood. There is something archaic about it and it fits in with these games with relics from ancient Rome as competition venues: the wrestlers compete in the ruins of the Maxentius basilica, the gymnasts whirl through the Caracalla baths, and the marathon runners start on the Capitol Square at the foot of the Mark-Aurel Equestrian statue. From there it goes over the Viale Cristofero Colombo and the Via Appia Antica to the Arch of Constantine.

Bikila has only been running a marathon for a few years. In the mid-1950s, the Finnish-Swedish track and field trainer Onni Niskanen discovered him in the bodyguard of Emperor Haile Selassie . And now this 28-year-old soldier is standing barefoot in the city that once led to two wars against his homeland. In 1896, with the first attempt at conquest, Abyssinian troops repulsed Italy’s army and preserved independence. In 1935, Mussolini’s men attacked with poison gas and occupied the East African country for six years. As spoils of war, the “Duce” had an ancient 24 meter high granite stele brought to Rome, the Axum Obelisk.

The fascist regime has long since perished, the obelisk is still there. Bikila passed it twice on September 10, 1960. Early on, he was part of a six-person breakaway group. One after the other falls back, but Bikila runs apparently effortlessly, as if weightless. Now the commentators are also wondering who this Ethiopian is who hurries ahead with small, quick steps on bare feet.

“That wasn’t a marathon, it was Aida”

When Bikila started with the marathon, Ethiopia was far from being a nation of runners, as Katrin Bromber explains. The Africa scientist from the Leibniz Center for the Modern Orient in Berlin is researching the social history of sport in Ethiopia. “While boxing, cycling, weightlifting, table tennis and ball sports were already part of the repertoire, the country’s first marathon did not take place until May 1954,” says Bromber.

Only a handful of athletes competed, two years later there were 15. The winning time was 2:45 hours, almost half an hour above the world record at the time. But since it was achieved at an altitude of over 2000 meters, the newspaper “Ethiopian Herald” speculated in 1956 : “With appropriate training and more experience in road races, we can certainly look forward to an international marathon victory.”

Four years later, that victory seems so close. At dusk, Bikila runs towards the Via Appia with his last pursuer, the Moroccan Rhadi Ben Abdesselam. Two thin shadows that – past hundreds of torchbearers – scurry across the ancient pavement. “It wasn’t a marathon,” wrote the newspaper “Corriere della Sera” later, “it was Aida, and the Roman roadside formed the choir.”

As soon as they have passed the obelisk for the second time, Ben Abdesselam also falls back. Bikila runs towards the Arch of Constantine, which is brightly illuminated against the night sky. After 2:15:16 hours he crossed the finish line in a new world record and briefly raised his right arm. While he is stretching under the triumphal arch, as if he had just come from the evening run, the news spreads over the radio around the world: A barefoot Ethiopian triumphs at the Olympics in Rome.

1960 was the “African year”

“Because of the colonial past, this victory had great symbolic power,” says Ansgar Molzberger, sports historian at the Cologne Sports University. “Although Bikila never particularly emphasized it in interviews, the message was clear: ‘I win here on your streets, even without shoes’ – basically a humiliation of the former oppressors.” The audience was amazed and fascinated.

Bikila is the first African Olympic champion to be born south of the Sahara. His barefoot victory is a sporting sensation – and has something almost prophetic about it. Because the year 1960 later goes down in history as the “African Year”, in which 18 African states threw off the chains of colonialism and achieved their independence. And at the same time, with Abebe Bikila, the era of success for East African long-distance runners began.

Back then – at least in Ethiopia – running was far from being the mass sport it is today, says Katrin Bromber. For the state power, however, it brought the hoped-for gain in prestige. “Emperor Haile Selassie recognized the importance of sport for the education of young people very early on, but above all for the recognition of Ethiopia as a modern state,” says the researcher. “First and foremost, Bikila’s success raised the self-esteem of the emperor and all those civil servants and sports officials who wanted to anchor Ethiopia on the international stage through sporting success. This was a very important factor during the Cold War and the wave of independence on the African continent.”

According to Bromber, it is difficult to say what was popular with the people of Ethiopia: “Radios were rare, television did not yet exist. Over 90 percent of the population lived in rural areas at that time, most of them were illiterate and certainly had other concerns than success in sport to celebrate.” Bikila himself, however, saved his life with his Olympic victory. “As a member of the Imperial Body Guard, he was directly involved in the violent coup attempt in December 1960,” says Bromber. “Instead of having him executed like many others, the emperor pardoned him.”

Seriously injured in a car accident

Four years later, the Games seem to be very far from Rome: Skyscrapers and streets made of rough, gray asphalt shape the picture in Tokyo. And Abebe Bikila, who started in white running shoes instead of barefoot in 1964. After his triumph in Rome, international sports equipment suppliers fought for him, because nothing made them appear more superfluous than a barefoot gold runner.

When Bikila turns into the Olympic Stadium in Tokyo, the 80,000 spectators cheer. Although he had only had an operation on the appendix a few weeks earlier, he is even three minutes faster than in Rome – another world record. His closest pursuers don’t reach the goal until four minutes later. The “Zeit” wrote afterwards: “He achieved a triumph for the first time, which even Zatopek tried in vain to achieve , namely to cross the finish line twice in the murderous marathon.”

However, Bikila’s third attempt at Olympic gold failed in Mexico in 1968 when he had to give up after 15 kilometers due to a fatigue fracture. His compatriot Mamo Wolde wins. Ethiopia’s sports journals continue to report on Bikila’s life, especially after his 1969 car accident, which he survived seriously injured. The following year, paraplegic, he took part in the World Disabled Games as an archer.

At the Olympic Games in Munich in 1972 he was invited again as a guest of honor and was celebrated by the public. It is his last major international appearance. On October 25, 1973, Abebe Bikila died at the age of 41 from the long-term effects of his accident.

A shining example for many other runners

Despite numerous Ethiopian successes, it took until the 1990s for running to become the number one competitive sport there. Today, Ethiopians and Kenyans seem to dominate the long haul at will. Meanwhile, the theory that East Africans have genetic advantages is not proven by any scientific studies, wrote the British-South African political scientist and historian Gavin Evans in his book “Skin Deep. Dispelling the Science of Race”.